Enterprise Software Solutions: A Data-Driven Guide to Defensible Vendor Choices

Enterprise software solutions are the core systems that manage everything from finance and logistics to customer relationships. These are not just tools; they are significant capital investments that define a company’s operational model and competitive posture.

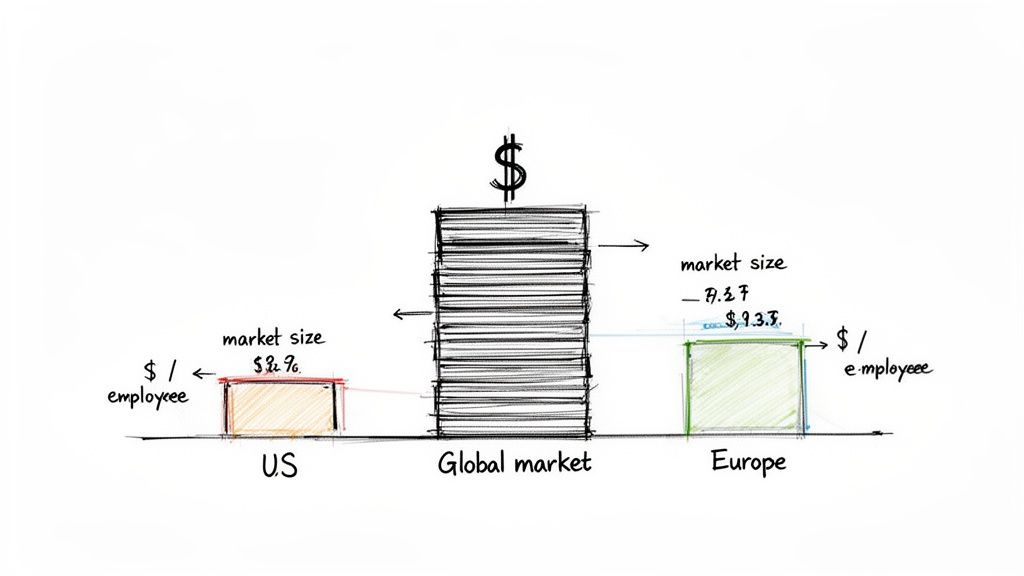

Before detailing the categories, we must address the economics. Understanding the scale of this market is the first step toward making a defensible investment decision.

Decoding the Enterprise Software Market

Discussions about enterprise software often hide behind vague terms like “digital transformation.” The reality is simpler: these are economic decisions, frequently involving nine-figure budgets where a single misstep can stall a company for years.

The financial stakes are significant. As a technical leader, you are under constant pressure to justify every dollar.

To put this in perspective, let’s examine the numbers.

Enterprise Software Spending at a Glance

The following table breaks down key market statistics. This data provides the financial context for every build-vs-buy conversation and vendor negotiation.

| Metric | Projected Value | Key Insight for Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size | $403.90 Billion by 2030 | The market’s substantial growth means delaying investment decisions can result in falling behind a global standard. |

| 2024 Global Spend | $899.9 Billion | This broader figure, including infrastructure and security, shows enterprise solutions drive significant secondary investments. |

| US Spend per Employee | $868.40 per year | US firms invest heavily in productivity tools, setting a high competitive bar for operational efficiency. |

| EU Spend per Employee | $157.90 per year | The 5.5x lower spend in Europe indicates a different operational philosophy, potentially creating opportunities or risks. |

This data shows that software spend is a direct reflection of a company’s strategic priorities and competitive intensity, not just an expense line item.

A Tale of Two Markets: US vs. Europe

The most revealing statistic is the spend-per-employee. U.S. companies invest an average of $868.40 per employee on these tools annually. In contrast, their European counterparts spend just $157.90.

That’s a 5.5x difference.

This isn’t a minor variation; it reveals a fundamental split in operational philosophy. The aggressive U.S. spending indicates a reliance on specialized software to automate processes, drive productivity, and gain a competitive edge.

For a CTO in the U.S., this data is critical context. You are not just buying a new CRM. You are competing in an arena where rivals invest heavily in technology as a primary tool for growth. Failing to keep pace is not a technical problem—it is a market-share problem.

The Real Cost of Falling Behind

The pressure to spend is intense, but the risk of choosing the wrong solution is greater. When a major software project fails, the loss extends beyond licensing fees.

The real costs include thousands of wasted consulting hours, stalled business initiatives, and the opportunity cost of having your best engineers tied up in a failed implementation for a year or more.

This is why the optimal decision is not always to buy the newest platform. Often, the most prudent financial move is a careful modernization of technology you already own. This shifts the conversation from acquiring new systems to maximizing the value of existing assets.

Understanding these financial realities is the foundation for navigating the complex world of enterprise software.

A Practical Framework for Software Categories

To make sense of the enterprise software market, you need a functional map, not a glossary of vendor acronyms. Marketing jargon is often designed to obscure function, making it difficult to match a business problem to the right software category.

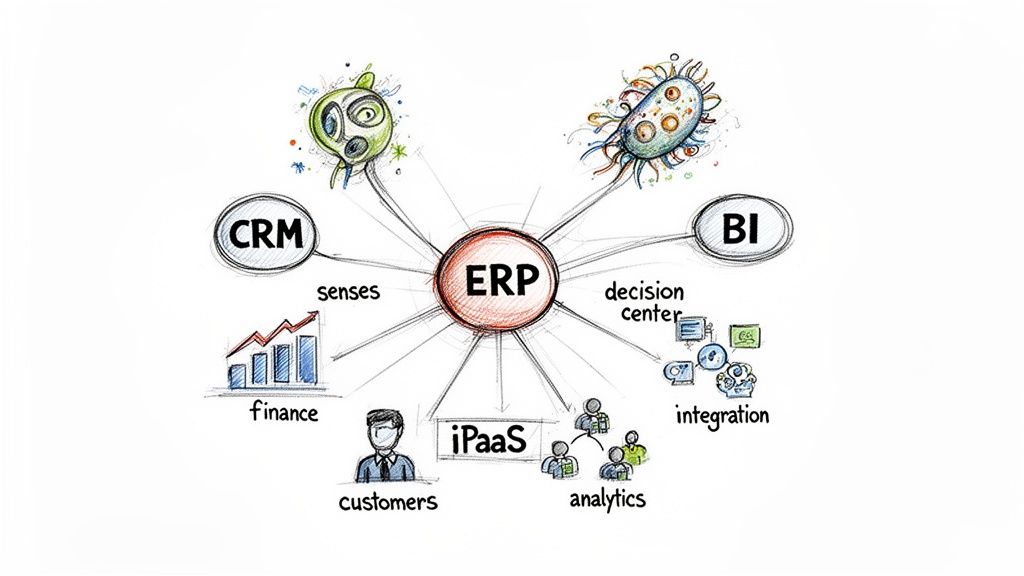

A better way is to think of your company as a living organism.

Each software category serves a distinct function. This mental model helps pinpoint which system is failing—or missing—when a specific business process stalls. Without this clarity, teams often purchase software to treat a symptom, not the root cause.

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): The Central Nervous System

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems are the operational backbone of a business. They run core, internally-facing processes that must be reliable and auditable—such as finance, HR, and supply chain. An ERP doesn’t just track money; it consolidates every department’s critical data into a single source of truth.

Think of an ERP as your company’s central nervous system. It handles essential, involuntary functions without which the business could not operate.

- Core Function: Integrates and manages foundational processes like finance, human resources, supply chain management, and manufacturing.

- Business Problem Solved: It eliminates data silos. Financial reports reflect real-time inventory levels, and production schedules align with supply chain logistics because all departments work from the same data.

- Primary Stakeholders: CFOs, COOs, and heads of supply chain or manufacturing. Their roles depend on the integrity of ERP data for forecasting and operational control.

A poorly implemented ERP is like a pinched nerve. Signals get crossed, inventory data becomes unreliable, financial closes are delayed, and the entire organization seizes up from a lack of coordination. The impact is felt everywhere.

Customer Relationship Management (CRM): The Senses

While ERPs handle internal machinery, Customer Relationship Management (CRM) platforms manage interactions with the outside world—your customers. These systems are built to capture, track, and analyze communications and activities across the entire customer journey.

If the ERP is the nervous system, the CRM is the five senses—sight, sound, touch—gathering intelligence from the market.

- Core Function: Consolidates all customer data and interactions across sales, marketing, and customer service into one platform.

- Business Problem Solved: It prevents different teams from having disjointed conversations with the same customer. A salesperson can see a support ticket’s status, and a support agent can see a customer’s purchase history, leading to a unified experience.

- Primary Stakeholders: VPs of Sales, Chief Marketing Officers, and heads of customer support who use it to drive revenue and customer retention.

Integration Platforms (iPaaS): The Circulatory System

Few modern enterprises run on a single software suite. Most use a mix of applications. Integration Platform as a Service (iPaaS) solutions act as the connective tissue, ensuring data flows cleanly between these disconnected systems.

This is your company’s circulatory system. It carries vital data (the oxygen) from one system to another, ensuring every part of the business gets the information it needs.

For example, when a new deal closes in your CRM (like Salesforce), an iPaaS solution can instantly trigger an invoice in the ERP (NetSuite) and add the new customer to a marketing campaign in Marketo without manual intervention.

- Core Function: Enables the design, build, and management of APIs and workflows that connect different software applications, whether in the cloud or on-premises.

- Business Problem Solved: It eliminates manual data entry between systems, which reduces human error and maintains data consistency. It is a solution for brittle, custom-coded integrations that break when a vendor updates their API.

- Primary Stakeholders: CIOs and IT architects. They are responsible for the overall technology landscape and ensuring data flows where it is supposed to.

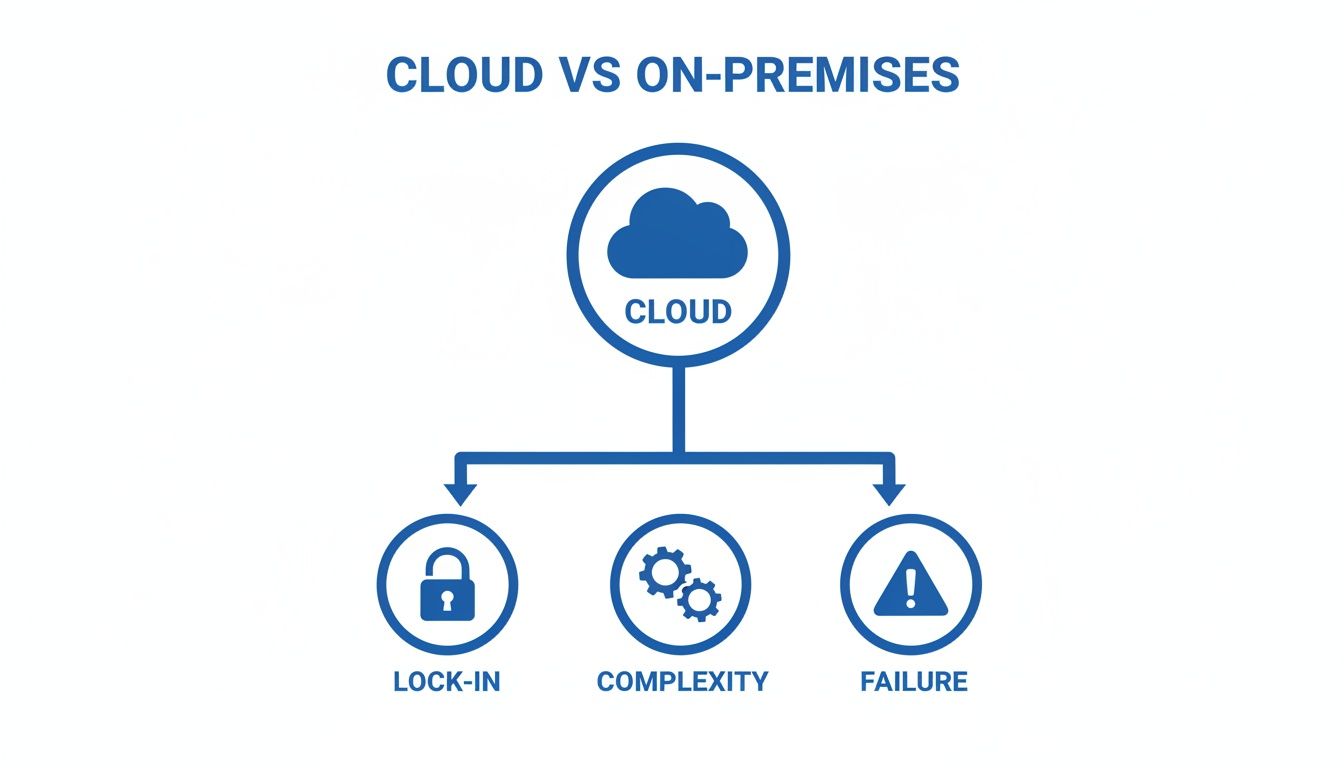

Navigating Cloud Dominance and Its Hidden Risks

The move to cloud-based enterprise software is the default strategy, not a trend. On-premises deployments are now the exception, displaced by the promise of scalability, no upfront hardware costs, and faster time-to-market. The data validates this shift.

Cloud deployment accounted for over 55% of the enterprise software market in 2024. According to Fortune Business Insights, the market is projected to reach $517.26 billion by 2030, growing at a 12.1% CAGR. North America leads with over 41% of the market share as large companies continue to decommission on-premise servers. However, an estimated 67% of these modernization projects fail, often due to technical oversight.

The foundational choice is not just about selecting a vendor; it’s weighing the trade-offs between cloud vs on-premises solutions. While cloud providers promote agility, prudent leaders must look past the marketing and understand the second-order effects of that decision.

The Realities of Vendor Lock-In

A significant risk in the cloud is not a security breach, but economic entrapment. Cloud platforms are designed to make entry simple and exit prohibitively expensive. This vendor lock-in is not just contractual; it is technological.

- Proprietary APIs and Services: Building an application around a service like AWS Lambda or Azure Cosmos DB tethers your architecture to that vendor’s ecosystem. Leaving often requires a near-total rewrite.

- Data Egress Costs: Ingressing data into the cloud is typically free. Extracting it is not. Egress fees can cost hundreds of thousands for large datasets, creating a financial barrier to switching providers.

- Institutional Knowledge: Engineering teams become experts in one cloud’s tools and certifications. This creates organizational inertia, as retraining on a new platform is a significant undertaking.

This creates a power imbalance. Once a provider knows it would be costly for you to leave, they hold leverage during contract renewals.

The Myth of Predictable Cloud Spending

A common misconception is that cloud spending (OpEx) is easier to manage than server procurement (CapEx). While you avoid large upfront hardware bills, you trade them for a different financial complexity that is frequently underestimated.

Cloud providers want you to over-commit on Reserved Instances. The discounts are attractive, but they require you to predict compute needs one to three years in advance. Overprovision, and you pay for unused capacity; underprovision, and you are pushed to more expensive on-demand pricing.

Managing cloud costs is a continuous discipline known as FinOps. Without it, bills can escalate from misconfigured services, unmonitored data transfers, or inefficient code. Running a thorough cloud migration risk assessment is a critical financial step to take before signing a contract.

New Failure Modes in a Cloud-Native World

Cloud platforms offer resilience but also introduce new and complex failure modes not typically seen in a traditional data center. The abstraction that makes the cloud convenient can also obscure the root cause of an application failure.

Key Cloud-Specific Risks:

- Misconfigured IAM Policies: In an on-prem environment, a firewall is a primary defense. In the cloud, a single incorrect Identity and Access Management (IAM) rule can expose sensitive data to the public internet.

- Cascading Service Failures: Your application’s uptime depends on the provider’s underlying services. When a core service like Amazon S3 or a DNS system experiences an outage, it can trigger widespread failures beyond your control.

- Regional Dependencies: Deploying all resources in a single region or availability zone creates a single point of failure. While multi-region architectures mitigate this, they add significant cost and complexity.

Moving to the cloud is not a simple “lift-and-shift.” It requires a fundamental change in how you approach architecture, security, and financial governance. Failure to adapt means trading one set of problems for another, often more expensive, set of risks.

A Defensible Framework for Vendor Evaluation

Choosing the right enterprise software depends more on long-term viability than on a vendor’s feature list. The standard Request for Proposal (RFP) process is often a box-checking exercise that prioritizes advertised features over architectural soundness and the true cost of ownership.

Making a defensible decision requires an evaluation framework that goes beyond the sales demo. It involves scrutinizing the technical, financial, and strategic realities of a partnership that will likely last five to seven years. This means asking direct questions that reveal a vendor’s true operational model.

Pillar 1: Technical Architecture and Integration

The software’s underlying architecture will dictate its flexibility and lifespan within your company. A sleek UI can mask a rigid, monolithic core that will constrain your development teams.

Focus on non-negotiables: scalability, API completeness, and the data model. If the platform cannot handle a 200% spike in traffic without re-architecture, it’s a liability. If its APIs are poorly documented or missing critical endpoints, you are committing to years of building and maintaining brittle custom connectors.

Key Questions for Vendors:

- API Access: Can you provide your full REST API documentation? What are your rate-limiting policies, and what percentage of the application’s core functionality is exposed via API?

- Data Model: Can we review the entity-relationship diagram (ERD)? How difficult is it to extend the core data model with our custom fields and objects without voiding the support contract?

- Scalability: What is the largest deployment you have in production, measured by concurrent users and transaction volume? What specific performance tuning was required?

Pillar 2: Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

The initial quote is an incomplete figure. The initial license fee for enterprise software is often less than 30% of its total cost over five years. Focusing only on this number is a common and costly evaluation failure. A realistic analysis must map every cost, from implementation through decommissioning.

As this diagram shows, a move to the cloud, often positioned as a cost-saving measure, introduces hidden complexities. Vendor lock-in, operational overhead, and integration failures are risks that can inflate TCO calculations.

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) includes implementation fees, data migration, employee training, annual maintenance, and the cost of third-party consultants required for customizations. It is the financial story of the software’s entire lifecycle.

Pillar 3: Vendor Viability and Your Exit Strategy

You are not just buying software; you are entering a long-term partnership with the company that builds it. The vendor’s financial health, product roadmap, and partner ecosystem are direct indicators of the risk you are assuming.

Is the vendor unprofitable or a likely acquisition target? If so, your platform could be declared “end-of-life,” forcing an unplanned and expensive migration. Our comprehensive vendor due diligence checklist provides a structured way to get these answers.

Equally important is planning your exit before signing the contract. An exit strategy is prudent business practice. How easily can you extract your data and move to another platform in five years? This should be a primary factor in your decision. Vendors that make data extraction opaque or expensive are building a cage, not a partnership.

Critical Questions for Your Team:

- Vendor Health: Is the vendor profitable? What is their funding situation and financial runway?

- Roadmap Alignment: Does their public roadmap for the next 18 months align with our strategic goals, or are they pivoting to a different market?

- Data Portability: What is the documented process for a full data export in a non-proprietary format (e.g., CSV, JSON)? What are the associated costs, and are they specified in the contract?

Thinking through these pillars forces a level of scrutiny beyond a simple feature comparison. The scorecard framework below can guide your internal discussions and vendor interviews, helping you cut through marketing and assess whether a vendor is a partner or a liability.

Vendor Evaluation Scorecard Key Questions

| Evaluation Pillar | Critical Question for Vendor | Red Flag Example |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Viability | ”Show us the API documentation for a common workflow, like creating a new customer and an order." | "Our APIs are only available to paying customers post-contract,” or providing vague, incomplete Swagger docs. |

| Total Cost of Ownership | ”Provide a sample SOW from a customer of similar size, including all implementation and customization line items." | "Every implementation is unique, so we can’t provide that.” (This may indicate costs are hidden until after contract signing). |

| Vendor Health | ”What percentage of your revenue comes from new licenses versus existing customer renewals?” | A high dependency on new sales (e.g., >70%) can suggest a “leaky bucket” customer base with high churn. |

| Exit Strategy | ”What’s the documented process and cost structure for a full data export if we choose to terminate our contract?" | "We can provide a database backup, but the data schema is proprietary,” or charging punitive fees for data extraction. |

Using this framework shifts the power dynamic. You become a forensic investigator uncovering the truth about a potential long-term partner, which is the only way to make a decision that is defensible over time.

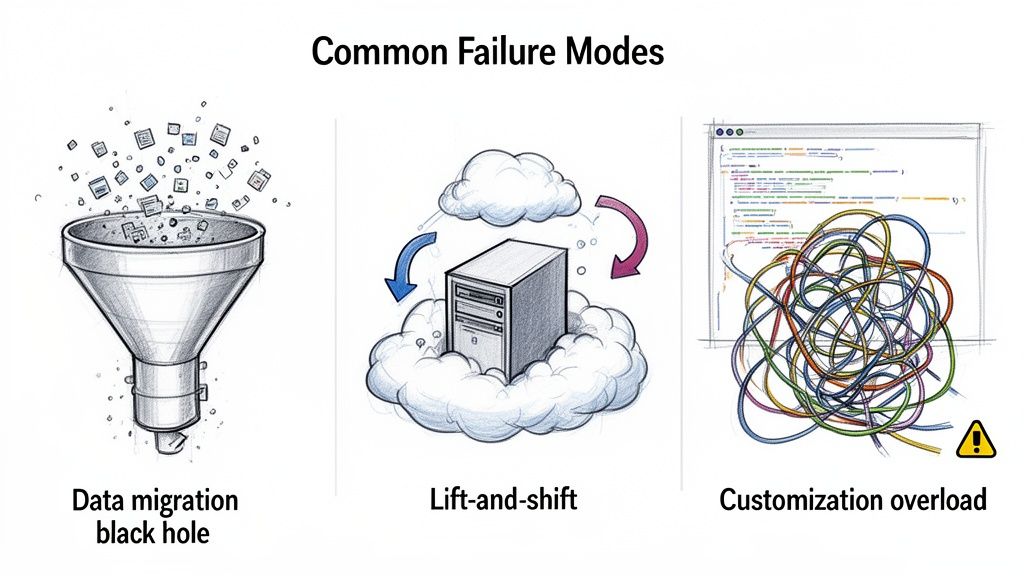

Common Failure Modes and How to Mitigate Them

Enterprise software projects typically fail slowly, through budget overruns, extended timelines, and low user adoption. The goal is not to avoid every issue, but to anticipate where problems are likely to arise.

The scale of investment is large. Gartner projects the market will hit $2,248.33 billion by 2034. Yet, complexity contributes to a high failure rate, with an estimated 67% of modernization efforts failing to deliver. The cause is often a technical oversight, such as the loss of precision when moving financial data from a COBOL system. You can review software market projections to understand the scope of the challenge.

Let’s dissect the three most common reasons these projects fail.

The Data Migration Black Hole

Data migration is often underestimated as a simple ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) task. In reality, it is a frequent point of failure for modernization projects. The danger is not a missing field, but subtle data type mismatches that corrupt financial data.

A classic example is migrating from a mainframe to a Java-based platform. Mainframe COBOL often uses a fixed-point decimal format called COMP-3 for currency, which is precise. Java’s standard double primitive type uses floating-point arithmetic, which can introduce small rounding errors.

The impedance mismatch between fixed-point and floating-point numerical representations necessitates careful handling. A direct conversion can turn a value like

$100.25into$100.249999999997, causing reconciliation failures that can halt a project.

This is a known issue that has caused significant financial and project-related problems for companies.

Mitigation Strategy:

- Demand Code-Level Proof: Your partner must demonstrate how they handle these conversions. In the COBOL-to-Java scenario, the appropriate solution is to use Java’s

BigDecimalclass, which is designed for exact monetary calculations. Do not accept vague assurances. - Test Early and Aggressively: Do not wait for the final cutover. In the first month, migrate a small but representative subset of production data and run parallel financial reconciliation reports. This will expose precision bugs while they are still inexpensive to fix.

The Lift-and-Shift Cost Trap

“Lift-and-shift” is marketed as a simple cloud migration strategy: clone on-prem servers as virtual machines in AWS or Azure. The problem is that this approach also migrates inefficient on-prem habits, for which you now pay a premium.

On-prem servers are typically provisioned for peak capacity and run 24/7. Replicating this architecture in the cloud is financially inefficient. You end up paying for idle compute, under-optimized databases, and internal services that now incur data transfer fees.

Your cloud bill becomes an itemized receipt of your technical debt. As a result, costs often increase by 30-50% compared to the previous data center.

Mitigation Strategy:

- Refactor, Don’t Replicate: Instead of lifting and shifting everything, modernize one critical component of your application. Move a monolith to containers or switch a database to a managed cloud service like RDS. This small win builds momentum and skills.

- Implement FinOps from Day One: Do not wait for the first bill. Implement cost management tools and a FinOps discipline from the beginning. Tag every resource, set up automated budget alerts, and make engineering teams accountable for the cost of the services they run.

Customization Overload and Technical Debt

Every enterprise platform requires some configuration. Failure often begins when “configuration” becomes “heavy customization.” It usually starts with a custom field or a tweaked workflow. Over time, this can evolve into a fragile, unmaintainable collection of proprietary code built on top of the vendor’s platform.

This custom code is brittle. Every vendor security patch or feature update becomes a potential breaking change for your custom logic. Your team is then caught in a cycle of re-testing and patching your own code, while the product roadmap stalls.

Mitigation Strategy:

- Establish a Governance Process: For every customization request, require the business owner to prove why a built-in feature or a small process change is insufficient. The default answer should be “no.”

- Isolate with APIs: If a customization is unavoidable, build it as a separate microservice that communicates with the main system through stable, documented APIs. This decouples your business logic from the vendor’s upgrade cycle, allowing you to apply patches without breaking custom functionality.

Building the Business Case for Not Buying

The enterprise software sales cycle is designed to create urgency. Sales teams often frame a decision not to buy as a failure to innovate. In reality, the most financially responsible decision can be to wait, say no, or improve what you already have.

Building a defensible case for not buying requires a clear-eyed analysis of the problem you are trying to solve.

A new software purchase can be an expensive way to paper over a cracked foundation. A new CRM will not fix a broken sales process, and a new ERP cannot repair a flawed inventory strategy. It will only make existing chaos run faster, at a significant cost. Before taking a vendor call, map your current workflow and pinpoint the exact points of failure. If the root cause is a process issue, technology alone is not the solution.

When Modernization Outperforms Replacement

There is an impulse in tech to replace anything labeled “legacy.” This often ignores the value of stable, battle-tested systems that are reliable. Mainframe applications are a prime example. While often characterized as outdated, many of these systems have processed high transaction volumes with near-perfect reliability for decades—a level of stability many modern distributed systems struggle to achieve.

Consider these scenarios where a careful modernization effort is the superior financial and technical move:

- The Core Logic is Sound: The application’s fundamental business rules are solid and not expected to change. The problem may be a clunky UI or an inability to integrate with modern APIs, not the core engine.

- Performance is Already High: The system already meets or exceeds its performance benchmarks for its primary function, whether that’s batch processing or high-frequency transaction handling.

- The Risk is Unquantifiable: The data structures are so complex and poorly documented that migration carries an unacceptable risk of data corruption or catastrophic failure.

In these situations, a targeted project—like wrapping the legacy core with modern APIs or building a new front-end—can deliver 80% of the value for a fraction of the cost and risk of a full replacement.

Resisting a new purchase is about demanding a clear, measurable return on investment. The technical leaders who earn the most respect are those who can prove that the most effective solution is sometimes the one you already own.

Avoiding Resume-Driven Development

A final trap is “resume-driven development,” where a team’s desire to use new technology overshadows business needs. An engineering team might push for a microservices architecture using trendy tools, not because it solves a customer problem, but because “Kubernetes” and “Go” look good on a resume.

This is where leadership must provide oversight. When building the case against a new purchase, grounding the discussion in financial reality is effective. Using a tool like a software license cost calculator can shift the conversation from technical novelty to concrete business outcomes. A disciplined leader can differentiate between a solution that serves the business and one that primarily serves an engineer’s career path.

Burning Questions from the Trenches

Navigating the enterprise software landscape requires direct answers. Here are the tough questions technical leaders ask during the selection process—and our direct responses.

What’s the Single Biggest Mistake People Make When Buying Software?

Focusing on the sticker price. The most critical mistake is underestimating the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) by focusing on the initial license fee.

TCO includes implementation, data migration, customizations, training, ongoing maintenance, support, and eventual decommissioning costs. A solution with a low entry price can become expensive over its lifecycle if it requires extensive consulting or is built on a rigid data model. A thorough TCO analysis often reveals that a platform with a higher initial price can be the more prudent long-term financial choice.

How Should We Judge an Implementation Partner?

Evaluate the partner and the software vendor as two separate but connected entities.

For the vendor, assess their product roadmap, financial stability, and platform architecture. For the implementation partner, get more granular. Scrutinize their technical expertise with your specific technology stack.

A strong partner can salvage a mediocre software choice, while a poor partner can derail a best-in-class platform. Always ask for the resumes of the actual team members who will be assigned to your project, not just the sales engineers from the demo.

When Should We Build vs. Buy?

This decision comes down to one question: does this software deliver a unique, difficult-to-replicate competitive advantage?

For standard business functions like payroll or general ledger accounting, buying an off-the-shelf solution is almost always the correct choice. The long-term maintenance burden of a custom build is significant.

However, if the software is for a core, proprietary business process that differentiates you from the competition, a custom build might be justified. Even then, before starting from scratch, explore highly configurable PaaS/iPaaS platforms. They can provide a “custom” feel without the full technical debt of a bespoke application.

Making a defensible vendor choice requires unbiased, data-driven intelligence. Modernization Intel provides unvarnished truth about implementation partners—their costs, failure rates, and specializations—so you can select the right partner with confidence. Get Your Vendor Shortlist at https://softwaremodernizationservices.com.

Need help with your modernization project?

Get matched with vetted specialists who can help you modernize your APIs, migrate to Kubernetes, or transform legacy systems.

Browse Services